celebrating black history month with belle of louisville riverboats

There are so many powerful stories connected to Black Americans in the Ohio River’s history. This February, we wanted to bring some of them to light. Whether connected to the river, steamboats history or our own vessels, here are some of the people we have highlighted this month.

York

York Statue on the Louisville Belvedere, courtesy National Park Service

Born between 1770 and 1775, York’s story dates back to Louisville’s beginnings. Enslaved by William Clark, co-leader of the Corps of Discovery, York had no choice but to leave the Clark homestead at Mulberry Hill, located on the site of the modern-day George Rogers Clark Park, to venture into the unknown of the American West.

Due to the isolation of Mulberry Hill, York had learned many survival skills and was able to help in dangerous conditions. York was integral to the success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Native American tribes that met the Corps called him “Big Medicine.”

Despite his role in the Corps of Discovery’s safe return, York was forced to remain enslaved despite being believed to have advocated for his emancipation. Not much is known about York’s life after the Lewis and Clark Expedition, but rumors abound.

His story has been brought to the forefront in this century. In 2003, renowned artist Ed Hamilton created a statue of York that stands near the wharf, close to where York’s journey began at the Falls of the Ohio.

Thornton and Lucie Blackburn mural in Toronto, courtesy of The Dialog

Thornton and Lucie Blackburn

Thanks to a couple from Louisville who risked everything, Canada became the legal terminus of the Underground Railroad for many seeking freedom in the 19th century.

On July 3, 1831, Thornton and Lucie Blackburn departed from the Louisville wharf, approximately where the Belle of Louisville now docks. The couple made their way to Michigan by ferry, steamboat, and stagecoach. What the crowds of people around them that busy holiday weekend did not know was that Thornton and Lucie were embarking on a harrowing journey to self-emancipation.

They had both been enslaved by different families, but had recently wed. When the man who enslaved Lucie died leaving many debts behind, her being sent to New Orleans to a terrible fate was imminent. The couple decided to risk it all to avoid separation and the horrors Lucie faced.

The Blackburns settled in Detroit, Michigan for two years. There, they made friends in the free Black community and built a house. All was well until the day someone visiting from Louisville saw Thornton walking down the street and informed his enslaver, who had been looking for him. The couple was put in jail to await punishment.

However, they managed a daring escape to Toronto, Canada. The legal issues surrounding their case strengthened Canadian extradition law in a way that made the country a safe harbor for those seeking freedom. Thornton founded Canada’s first taxi company and to this day many Toronto-area cabs feature the colors he selected: red and yellow.

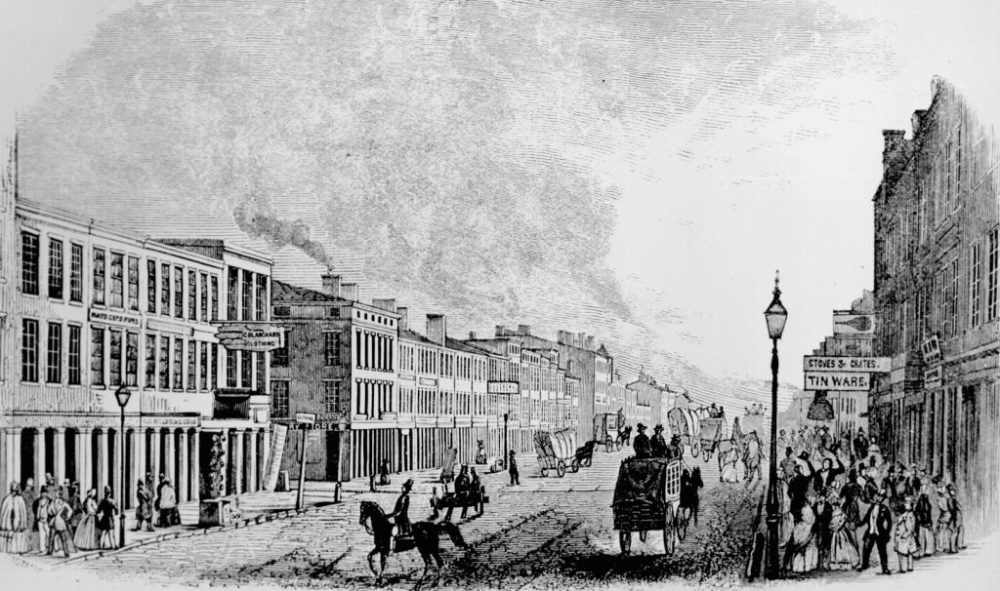

Louisville’s Main Street in the 1840s, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

James C. and James R. Cunningham

The story of the Cunninghams is the story of an extraordinary father and son who broke barriers in Louisville’s nineteenth-century music scene. James C. Cunningham was a free person born in the Caribbean in 1787. Cunningham was a violinist, and joined a music group in Louisville in 1835 before starting his own in 1847. “Cunningham’s Band” was a popular source of high-society entertainment in the city, and the band once performed for President-elect Zachary Taylor.

In between music gigs, James Sr. worked on riverboats, which provided opportunities to assist people seeking freedom via the Underground Railroad. He was accused of breaking the law by assisting up to six freedom-seekers in the 1850s. He was also known to smuggle abolitionist literature in his sheet music.

James R. Cunningham was James C. Cunningham’s son. A full-time musician by the age of 17, James Jr.’s band was known to play on the ice of the Ohio River when it froze over. It was highly likely that he played music on steamboats. He also went on international tour, becoming one of the first Black American musicians to tour in Japan and performing for Queen Victoria. Additionally, Cunningham performed for three U.S. presidents.

Shelton Morris

The Ohio River played a pivotal role in the Underground Railroad, and Shelton Morris is another example of someone who used his position as a steamboat worker to assist freedom-seekers crossing from states where slavery was legal to free states. Morris was enslaved by his own father, but when his father died, his entire family was emancipated and given some money. They relocated from Virginia to Louisville, where Morris was a barber and a wealthy landowner. After his wife died and he was accused of illegally voting in the 1840 election (Black Americans did not have the right to vote at the time), Morris moved to Cincinnati, where he worked on riverboats as a barber. Using their position on the border between Kentucky and Ohio, Morris and his brother-in-law Michael Clark (believed to be William Clark’s Black son) helped freedom-seekers make their way on the Underground Railroad as well.

Rudell Stitch Hometown Heroes Banner, courtesy Carnegie Hero Fund

Rudell Stitch

Moving ahead into the twentieth century, many locals remember how their parents worked with Rudell Stitch, or knew his children well. Stitch was born in 1933 in Louisville’s West End. He worked at a meatpacking plant on Shelby Street, but all his free time was devoted to his true passion: amateur boxing. After putting in long hours at the plant, Stitch would train at Bud Bruner’s gym on Shelby Street (located where Clayton & Crume is now in NuLu.) Some days, Stitch would wake up at 3:30 a.m. to run before work. A young Muhammad Ali would spar with Stitch from time to time to measure his progress.

After winning many amateur matches, Stitch was able to pursue boxing full-time starting in 1956. He took home five Kentucky State titles. In his off time, Stitch enjoyed fishing at the McAlpine Dam. One day, while he was fishing, he rescued a stranger, Joseph Shifcar, who was drowning in the Ohio River. For this, Stitch was awarded a Carnegie Medal. In 1960, Stitch tragically drowned while attempting to rescue someone else who had fallen in the river. He was awarded another posthumous Carnegie Medal for this heroic act.

Mural at Hudson Middle School, courtesy of Jefferson County Public Schools

J. Blaine Hudson

Myths about the Underground Railroad and Kentucky’s role in it abound. Some of the most groundbreaking scholarship that dispelled these myths was done by Dr. J. Blaine Hudson, who chaired the Pan-African Studies Department at the University of Louisville. Dr. Hudson’s work provided a great deal of background on some of the people we have talked about in this very blog post. Hudson himself was remarkable as well.

As a student at the University of Louisville, Hudson was once arrested for protesting for the creation of a Black Studies program and for better opportunities for Black students. He invested a great deal of his career at the University and ultimately became the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. As a scholar of the Underground Railroad, Dr. Hudson shed light on the ways that Black Kentuckians helped each other self-liberate, and that every Underground Railroad story was unique. He also advocated for the creation of Freedom Park on the University of Louisville’s campus, which celebrates Black History in our city.

After a community-wide vote, a new middle school opened by Jefferson County Public Schools in the 2023-24 school year was named Dr. J. Blaine Hudson Middle School, the first school opened in Louisville’s West End in 91 years.

There are countless stories that have yet to be told, and we are honored to get to share these with you as we celebrate Black History this month and every month.